ClayHound Web

- Cherokee

Pottery

ClayHound Web

- Cherokee

PotteryReturn to:

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Anna Mitchell |

|||||||||||||||

|

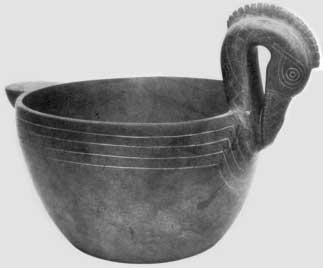

Cherokee potter Anna Mitchell has worked hard for more than 30 years on her pottery and has done much research to make it authentic. She is known today for creating Southeastern and Eastern Woodlands-style pottery, but faced a few obstacles when she began making pottery 34 years ago. There was no guide on creating Cherokee pottery, and few Cherokees were making pottery when she began creating objects from clay found in a pond near her home in Vinita, Okla., in 1967. After creating these small objects, including a pipe for her husband, Robert Clay Mitchell, she became curious about clay and how her Cherokee ancestors created their pottery. "I knew Cherokees hadn't really done pottery since removal, there wasn't anyone doing it or people who knew how to do it," Mitchell said. "But I thought surely it could be done again." When she realized the art of making Southeastern pottery was in danger of being lost, she became more determined to help preserve it. "I believe without art you don't have culture and without culture you don't have art," she said. Mitchell began studying tribal cultures and their artwork searching for instructions on making Southeastern pottery. There was very little. The knowledge of creating Southeastern-style pottery had lain "dormant" for many years, she said. She continued her studies and creating pottery through trial and error with encouragement from her husband.

"He was my partner in this when he retired from his job. He was very proud of his Cherokee culture and very helpful; the whole family was supportive. They all respected the fact that it was something I wanted to do. "My kids were in school, so I could spend time on my pottery during the day and on weekends, but I didn't do it every day," she said. "I really didn't know I was talented until I began doing this." Mitchell said there were times when she nearly walked away from making pottery, but "kept getting pulled back into it." She continued searching for information on Southeastern native peoples. A break came in 1973 while she was showing a few pieces of her pottery at the Indian Trade Fair in Tulsa. It was the first time she had publicly shown her work. At the fair she was introduced to Clydia Nahwooksy (Cherokee), then director of the Indian Awareness Program for the Smithsonian Institution Folklife Festival, who encouraged her to continue her work. Through this meetings she also gained access to the Smithsonian archives. Mitchell said it is likely she would have quit pottery if not for the encouragement she received at this time from Nahwooksy and others. Eventually she found a book entitled "Sun Circles and Human Hands," while doing research at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville. This book provided background and knowledge to create Southeastern pottery. Mitchell became an authority on Southeastern and Eastern Woodlands art. She learned Southeastern art had been dormant long before the Cherokee removal and other tribes' removal to the west. This was likely because these tribes had assimilated with their white neighbors much earlier than tribes in the west. Before contact, many Southeastern tribes traded and shared artwork designs, so she also realizes not all of her art may represent Cherokee designs. Too much knowledge was lost through assimilation to know for certain what were truly Cherokee designs, but she knows her designs are of the Southeast and Eastern Woodlands. She creates her pottery in a small studio near her home, and only works on her pottery in the warmer months, saving the fall and winter to spend time with her family. She usually works on three pieces at a time, working on them at different stages. Depending on the size of each piece of pottery, she said she can usually prepare a piece for firing in two weeks. She fires her pieces using wood behind her studio in an area surrounded by bricks. The clay pieces are placed on a metal sheet above the fire for an entire day. The pottery hardens over the fire and gradually cools as the fire cools diminishes. "I try to follow as much as possible what my ancestors did," she said. She decorates her pottery with leaves and other ornaments, which are placed on the outside of her pottery before firing. She has also created her own unique fired-clay stamps, which she uses to stamp different designs on her pottery before firing. Central American Indians used similar stamps, she said. She shows her creations at various art markets and has been traveling to the popular Santa Fe Art Indian Market in Santa Fe, N.M., for the last 14 years. In 1982, then-Oklahoma Gov. George Nigh, named Mitchell an Ambassador of Goodwill for the state because of her pottery work. "Things just happened" after that she said. She and other Oklahoma artists were invited to the Smithsonian's annual Folklife Festival the same year. A few years later, the Cherokee Nation named her a Living Treasure, and in 1988 a bronze likeness of her was dedicated at the annual Northeastern State University Indian Symposium to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the Trail of Tears. She was featured in a book by Lois Sherr Dubin entitled "North American Indian Jewelry and Adornment from Prehistory to the Present" in 1999. The book featured Indian artists from throughout the country, and Mitchell was featured in the Oklahoma and the Southeast artists section. All of these honors do not include the numerous awards she has won for her pottery over the years. She has placed in all pottery categories or has received honorable mention at the Santa Fe Indian Market each of the 14 years she has attended, which is no small feat considering the number of skilled pottery makers in the Southwest. "I've received honors for something I really enjoy doing," she said.

"I want students to learn culture when I am teaching them. I insist they learn it. They all have," Mitchell said. "She's easy to learn from, she's a very patient person," Vazquez-Mitchell said. "If you really want to do this it takes patience and some skill. It's not something you do in a hurry." What started from a lump of clay from a pond has opened many doors for Anna Mitchell. As much as she enjoys creating art and learning more about her culture, she cherishes the things that have come with being a recognized artist. "It's been the most wonderful adventure because I've met other people I never would have met otherwise. I've also met people from so many other tribes and got a chance to get to know other artists," she said. (from: http://www.cherokee.org/Phoenix/XXVno2_Spring2001/ArtCulturePage.asp?ID=1) See also: http://www.cherokee.org/Phoenix/XXVIno1_Winter2002/PhoenixPage.asp?ID=2 |

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

She

is thankful for her late husband's encouragement and help.

She

is thankful for her late husband's encouragement and help. Mitchell is hopeful the pottery making she reclaimed

from her studies will continue with the next generation. She has

taught pottery in schools through the Title IV Indian Education

Program and has been a cultural consultant at times. She has taught

apprentices over the years, first a nephew who will attend Yale

University next year to study medicine, and Cherokee artist Jane Osti,

who is now a well-respected artist herself. Mitchell has also shared

her artistic skills with her daughter Victoria Vazquez-Mitchell, of

Welch, Okla., who, in the two years she has concentrated on pottery,

is beginning to win awards for her own creations. She won a third

place ribbon for one of her pieces at last year's Santa Fe Indian

Market.

Mitchell is hopeful the pottery making she reclaimed

from her studies will continue with the next generation. She has

taught pottery in schools through the Title IV Indian Education

Program and has been a cultural consultant at times. She has taught

apprentices over the years, first a nephew who will attend Yale

University next year to study medicine, and Cherokee artist Jane Osti,

who is now a well-respected artist herself. Mitchell has also shared

her artistic skills with her daughter Victoria Vazquez-Mitchell, of

Welch, Okla., who, in the two years she has concentrated on pottery,

is beginning to win awards for her own creations. She won a third

place ribbon for one of her pieces at last year's Santa Fe Indian

Market.