ClayHound Web

- Kumeyaay

Pottery

ClayHound Web

- Kumeyaay

PotteryReturn to:

|

Kumeyaay is located in the area of San Diego, California. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

We've been told about several Kumeyaay potters. Teresa Castro is the sister of Margarita Castro and grand-mother of Maricela Carrilo. Margarita has 2 daughters Tirsa Castro and Celia Flores Castro. They both make pottery. Tirsa signs her pots TFC sometimes. Celia and her mom's pots are nearly indistinguishable. In addition, Daria Marescal, a decent potter, she tends to make experimental pieces instead of doing the traditional styles. Manuela Aguiar and her sister Teresa Aguiar. They are elderly widows and live together. They usually pot during the summer and work on baskets, dolls, net bags during the winter. And Eva Salazar, who is Kumeyaay/Paipai/Kiliwa makes clay dolls and occasionally pottery .

The above information, the identification of the unsigned pot and the above photo comes from JB Kingerly, husband of Eva Salazar and collector of old Mohave, Maricopa effigies, Quechan (Yuma), Cocopah and Kumeyaay pottery and baskets. See also: http://www.howka.com/ - California Indian Arts & Crafts in Old Town, San Diego How Kumeyaay Pottery is Made Items of clay are made and used in the traditional way. Pots are used for cooking; storing water or seeds; and eating (small bowls, spoons, cups and pitchers). The clay (color ranges from tan-brown-red) is dug from the hillsides and ground in a metate with a mano stone. Water is added, the clay kneaded and then it wrapped or placed in a container to cure for several weeks. Once ready, it is formed into a small ball, then flattened. It is placed upon a small "anvil" or the bottom of another pot and gently patted with a wooden paddle to shape it and to remove air bubbles. A thin cloth is used to cover the anvil or pot and make the clay easier to remove later. It is left to dry and harden before it is removed from "anvil" or bottom of the pot. More clay is added in stages as coils which are patted into position and shape. It is frequently set out to dry and become firm as it gets larger. A smooth stone is used to burnish the surface. The pot is left to dry several days and then fired in a pit in the ground. The natural markings "fire clouds" are from the smoke and fire. (information from Mission Trails Regional Park in San Diego) |

|

|

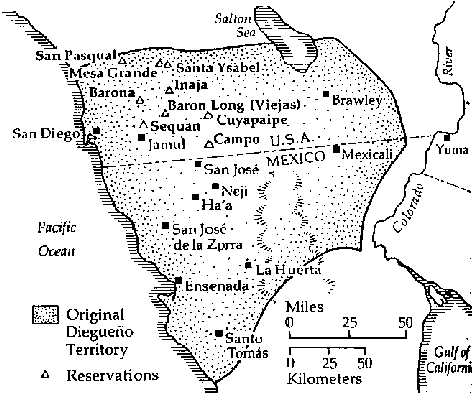

The term Kumeyaay was coined by native people and F. Shipek in the 1970s and is all inclusive of Diegueño and Kamia, the Yuman-speaking Indians of Imperial County over the mountains east of San Diego County. The Kumeyaay were seasonal hunters and gatherers whose individual bands ranged along waterways from the San Diego coastal region, east through the Cuyamaca and Laguna Mountains to beyond the Salton Sea in the east, and south beyond current-day Ensenada in Mexico. Bands spoke individual dialects and lived a loosely connected lifestyle intermarrying among them. They fished in the bay, gathered grunion and mollusks on the beach, hunted small game like rabbits, picked wild fruits, berries and their staple acorns. They also engaged in primitive horticultural activities away from coastal regions. Each territorial band -- with a population of between 200 and 1,000 persons -- controlled approximately 20 miles of river drainage (depending upon the width and richness of the valley) from their winter home These bands are classified together as Kumeyaay because they are all of the Yuman language family, Hokan stock. (from: http://www.desertusa.com/mag99/july/papr/kumeyaay.html) |

|

|

The Kumeyaay Indians The following information was taken from "The

Kumeyaay Indians" by Roberta Ladastida & Diana Caldeira

in cooperation with the Campo Band Mission Indians - Title V Grant

(1995) San Diego County Office of Education. - see also: http://www.kumeyaay.info/ and http://www.kumeyaay.com/ Approximately 1,000 years

ago a people called the Kumeyaay lived throughout what is now

Hunters and Agriculturists They were hunters and agriculturists. Anthropologists have evidence that they cultivated various grasses for seeds and other plants, transplanted cactus, elderberries, oak and burned large areas to keep crops in control. Kumeyaay environmental specialists had observed which plants grew in response to oddly timed rains of drought years and increased those plants for drought emergency purposes. They also planted beans, corn, squash and other food sources in the desert and mountains, where running springs, summer rainfall, or the Colorado River overflow made such planting feasible. Usually the woman did the gathering of wild plants with the men assisting them in the more difficult harvesting. The men hunted large game animals such as deer or bighorn sheep as well as rabbits, or tapped small rodents, birds and reptiles as a supplement to their diet. In order to take advantage or ripening or a concentration of animals, the people moved with the seasons between one or two permanent villages and numerous camp sites. They traveled large areas, some from the coastal regions to the Lagunas or Mexico to gather acorns and pinon nuts. Indians from the desert area would travel the same network of trails. Other trails ran north and south from Santa Barbara to Baja California. Tom Lucas has traced many early trails on maps, Just Before Sunset, that were jointly used. Interstate 8 was one of those trails. Food The Kumeyaay's harvesting was done according to the season. Acorns and pinon nuts were collected in the fall from the Laguna mountains and the mountains of Baja California. Flowers, fruits, grain, seeds, stems, bulbs and roots were gathered in the spring and summer from the valleys, canyons and foot hills. Fish and mullusks were caught and dried, as were, rabbit, small rodents, birds, and of course, large meat animals as mountain sheep, antelope, and deer that were hunted year round. The Kumeyaay conservatively and religiously used the natural resources that were native to their area. Prayers and sage smoke were offered before harvesting and hunting. The natural resources not only provided food but, clothing, tools, shelter, medicine and religious purpose. Water Water was the basis for life. Therefore, the Kumeyaay built their dwellings near streams and rivers. Water was plentiful most of the time with much underground water available. Willows, water cress, reeds, cattails, deer grass, and juncus are just a few of the natural resources that grew along the banks of these waterways. The Kumeyaay kept springs clean, and used various means to guide water to their crops and protect the land from erosion. They constructed rock and brush dams, levees, and ditches on level land, and on slopes, constructed rock terraces across the slopes to spread and slow water flow. Tools These people used the natural resources of plant, wood, rock, shell and bone to provide tools for domestic duties, the hunt, and provide safety for their families. The Kumeyaay were not aggressive people but did make a wooden club with a sharp carved handle to be used in battle if needed. They also made bow and arrows for hunting and protection. Rabbit sticks (throwing stick like a boomerang) were used for killing small animals. Long digging sticks were used as carved utensils for various purposes. They made knapped arrow heads and scraping tools from obsidian and other hard rock. Indians to the south used wooden arrows heads and it is possible that the Kumeyaay also used these in prehistory. Rocks served many purposes. Rock arrow shaft straighteners were used. The metate, ground mortar and pestle were used to grind the seeds and acorns to provide the flour for acorn mush (she'wii ) and breads. Awls for piercing holes in baskets, leather and shells were made from animal bone. Shells provided trade items, jewelry, bowls and fish hooks. Nets were woven from jucca, agave and milkweed to catch small animals and birds. Nets and woven sacks were also made for storage or to carry belongings. One such burden net ( hapuum ) was placed across the forehead to carry articles supported on the back. Village Imagine if you will, many

domed willow branch dwellings scattered along the streams and valleys.

If the village was by one of the bays or lakes you would see canoes or tule balsas with men fishing. Double bladed paddles were used to guide the canoes of balsas and some were pushed with long poles depending on the water site. Padre Junipero Serra described the Indians of the area in 1769: "Located at this same site is a gentile rancheria whose people it is a pleasure to meet. They are fine in stature and carriage, affable and gay. They have indeed endured to us. They brought fish and mollusks to us, going out in their canoes just to fish for our benefit. They have danced their native dances for our entertainment." Their homes were made from the willow trees that grew so abundantly in the area. The dwellings were circular domed structures woven from willow branches that still had the leaves attached. There was a small door opening and a large basket or woven mat would be pulled over it at night to keep the cold air out. Sometimes a small fire was built within the structure for warmth. A rabbit blanket was also used as a soft warm covering and grasses were used to soften the floor. Cooking was done outside in fire pits. A sweat house was used by the men of the village. It was similar to the dwelling but smaller. It served as a place to meet and cleanse oneself physically and spiritually. A fire provided the heat. Today men and women use the sweat houses for purification purposes. There was a space of religious gatherings, usually round and surrounded by a fence or brush. There was another smaller circular area for the dancers. Observers could see over the fenced area. Clothing Plants and animals also provided clothing. The Kumeyaay women wore the afore mentioned willow bark skirt (pounded strips of willow bark) which was sewn into two apron pieces and tied on, one to the front and the thicker longer one tied to the back. Baskets hats were worn by men and women to protect their foreheads from the trumplines of the agave carrying nets and could be used as cups for water when they needed it or for carrying items. There were plain or decorated and used for adornment. Men and women wore their hair long. The men bunched it on the crown of their heads or wore it loose. Kroeber says the women wore bangs. If a family member died, it was part of the mourning process to cut all family members hair short. This custom is still carried out today by some Kumeyaay. The hair was kept for special ceremony held a year after the cremation of the diseased. Men wore no clothing or a woven agave belt to hold the hunting tools he needed. In cold weather a twined/strip rabbit fur blanket was worn by men and women. They wore agave fiber sandals for rocky or thorny areas but usually went barefoot. Women's chins were tattooed, ukwich, with two or three lines during the adolescence ceremony. Some experts suggest this was to visually display family lines for marriage purpose and Tom Lucas mentions this regarding the Yuma Indians. They used a cactus thorn or other sharp tool to poke small holes in the skin and charcoal was rubbed into it to color it. Foreheads, cheeks, arms, and breast were sometimes tattooed. Men sometimes were tattooed on the legs. Painting the face and body were also used for body decoration and ceremonial purpose. Social Structure The Kumeyaay nation was organised into territorial hands and each controlled approximately 10 to 30 miles of river drainage, depending upon the width and richness of the valley. Each band also had rights to certain coastal and mountain areas for access to resources in those environments. Each band's population was between 200 and 1,000 persons, again varying with the richness of the valley. Most band members lived spread along the valley at small side drainages or springs in extended family groups on their own land so there was large amounts of area between each family group. The captain or leader (

kwaaypaay ) was born to his position or selected because of ability to

lead. His job was to lead the people and pass on duties that were

needed. He handled disagreements and acted as an overseer for the

benefit of the people with help of a council. Assistant leaders in the

band structure were called koreau . There was a council of religious

and environmental specialists who managed the economy for the benefit

of the band. Each band had a central village where the kwaaypaay and

religious leaders lived and managed the ceremonial center. Kinship System When a man and woman were married the woman kept her lineage name. Her children took the name of the father's lineage, according to The Indians of Southern California, S.D.M.M. Handbook. The woman went to live with the man's family band. Family titles were different as stated by Virginia Landon. Children of mother's sisters and of father's bothers were called brothers and sisters. Children of mother's brothers and father's sisters were called cousins. The kinship system crosscut the band structure. When relationships were known, individual used specific kin terms (aunt, uncle, grandfather, etc.) and those traceable relatives were called shimull. Each band had lineage groups (traceable kin) from 5 to 10 shimull. Members of a shimull could trace their ancestry back for 5 generations, beyond that they considered themselves related but through some unknown ancestor. The Kumeyaay had relatives in most bands and would visit relatives throughout the territory. Religion The religious year was observed by solstice and equinox ceremonies, all managed by the kuseyaay or shaman. The kuseyaay were born to their calling. Boys were watched to see if they had the innate qualities and interest for this duty. When a candidate was found, he was taught his duties, the knowledge of herbs, prayers, songs, ceremony organization, etc., by a kuseyaay. The kuseyaay were the healers of the village. They had great knowledge of herbal medicine and curing songs and ceremonies. The kuseyaay were also astronomers, knowing the movements of the stars through the seasons and phases of the moon. The personal ceremonies such as naming, puberty rites, marriage, and death were timed by the movements of the stars. Thus the kuseyaay's memory was remarkably prodigious Long ago the Kumeyaay cremated their dead, but because of the mission influences the deceased are buried today. The family cut their hair as a sign of mourning and this is practiced by some Kumeyaay today. It is noted in Kroeber that the Kumeyaay are the only California Indians that seem to "possess a system of color-direction symbolism. That is: East, white; south, green-blue; west, black; north, red." The ceremonial direction is east. The ceremonial numbers are in fours, for ceremonial repetition. Examples of this might be singing songs in patterns of four sets or initiation ceremonies lasting four days. Accounts of other ceremonies can be found in Just Before Sunset by Lora L. Cline and Handbook of the Indians of California by A.L. Krober. Ceremonial Art Various art forms were used during religious ceremonies. Sand painting has been noted in Kroeber. The Kumeyaay used realistic symbols drawn with varied colors of sand to explain their universe and creation origins. Prehistory rock art, petroglyphs (pecked or carved) and pictographs (painted) have been found throughout the Kumeyaay area as well as many Indian observatories or solstice sites. Cowels Mountain in one of these sites. Theories about the purpose of rock art abound, two are, puberty rites and religious purposes. The symbols are geometric in design as well as anthropomorphic which means animals or human shapes. The Forgotten Artists, Indians of Anza-Borrego and Their Rock Art, by Mandred Knaak, provides more information and photographs of this study. Music and Dance Music and dance were a part of the many ceremonies the Kumeyaay practiced. Songs were a respected part of the ceremonies. These songs retold stories of their history and creation. Some songs were very short with only a few repeated verses while others could last two days or more were extremely complex. Prayer songs were to provide for good hunts, seasons, and health of the people. Many of the songs were fun and entertainment. The songs and dances are still practiced today. The musical instrument used to provide the rhythm was usually the rattle. Some were made from gourds, called halmaa, with wooden handles and small rocks inside to produce the sound. Holes were added for decoration or resonance. Sometimes they were decorated with color and designs. Another type, called 'ehnally, was made from one to three turtle shells skewered underside through the back on a wooden handle. Rocks were inserted to make the sounds and the holes were plugged. The 'ehnally was used in ceremonies by the kuseyaay. Another type of rattle was made from deer hide that was formed into a hollow ball shaped attached to a wooden handle. The Kumeyaay's deer toe rattles were used during mourning ceremonies. These were decorated with feathers and bound with sinew. Flutes were also used to provide music. These were made from reeds with holes drilled in them to produce the sounds. Bull-roarers, flat, long carved sticks tied to a cord and swung over the head, were used for noise not rhythm. They were used to announce ceremonies and warn people away. It made a loud whirring sound. Dancing was an expression of the music and had patterns and style to accompany the various ceremonies observed. The modern pow-pow is a study in dance protocol, expression and style. Basketry The Kumeyaay, like all

California Indians, made the finest coiled baskets in the world. The

fine, tightly stitched baskets held water and were made in a variety

of shapes and sizes for many purposes. The baskets

Granary baskets were utilitarian and were woven from leaved branches of willow. They were much bulkier and could be made quickly. The baskets ranged in size from about one foot to four feet or more. The huge granary baskets were used to store the yearly harvest of acorns. These were raised on a platform made of logs and some were wedged in tree trunks. They were raised to protect them from insect, animals and possibly water damage. Some other baskets that were used for utilitarian purposes were winnowing (sifting) basket for sifting acorn meal of clay and loosely woven leaching (draining) basket for separating the tannin from the acorn meal. Leaves were put over the loosely woven basket, acorn meal put on top of the leaves and water slowly poured over the meal to leach out the tannin. The leaching basket could be made very quickly as uniformity and even surface was not attended to according to Kroeber. The Cahuilla, by Lowell John Bean, has excellent photos of the basket and pottery styles. Cradle-boards, called 'uukill,

can be put under the category of basketry as parts were woven or

twinned and the foundation was of lattice work. They were used to

carry the babies and keep them secure. The cradleboard could be hung

from a tree branch or braced against a boulder while the mother worked

and was carried on her back when she needed to travel. They were

constructed from willow branches and padded with pounded willow bark,

tules or soft grasses and covered with animal skins. The babies face

was protected by a woven shade cover and he was secured by soft straps

of animal hide or woven straps from from plant fibers. Pottery Pottery was also an important product of the Kumeyaay people. They used it to store food, to cook in and for storage of cremation remains. The Indians of the area would collect clay from their area be it from cliffs or river banks. Some clays ranged in color from beige to white, but most clay in this area is red or brown. They would grind and sift the clay using winnowing baskets as they did with the acorn meal. When the clay was clean and fine they would add water and mix it to the precise consistency. The they would use an old pot bottom to start the shape of new pot they were going to make. Once the pot reached the desired size it was carefully removed from the old form. More coils were added and a rock or clay anvil was used to hold the inside steady while the outside was pressed and paddled (wooden) gently into shape. The pots called ollas had wide mouths and other for water storage had narrow mouths with longer necks to prevent evaporation. The Kumeyaay produced mostly undecorated pottery. Fire clouds (black smoke patterns) were a natural firing decoration that made many pots attractive. If any decoration was to be used, it was painted on with a red oxide using a simple braided twine or plant fiber brush. The designs were geometric, dots, lines and on occasion stars. Once the pot was finished it was dried for three days. The women believed that the pot would crack if anyone saw them make it, so pottery was an isolated job. The pots would be fired in a shallow pit in the ground. Stones or logs were placed in the pit first as a floor. Then the pots would be laid upside down on the floor. Branches of oak or stalks of yucca (depending on the natural resource near by) would be placed over the pots and set afire. This was done at dusk and the pots would be taken from the ashes at dawn. Clay and stone pipes were made for ceremonial and personal use. A native tobacco was smoked. Some pipes had a ring inserted to support a card so they could be worn around the neck. There are small groups of Kumeyaay who have continued to practice the crafts of basketry and pottery. There is a resurgence of these crafts today and classes are being taught at the reservations with men, women and children attending. Games and Recreation The Kumeyaay enjoyed games. Many of the games the people played were practice of the skills needed in the village community, others were for fun. People took great pride in their endurance and skills. These games were played during the times the people came together for ceremonies, and the people looked forward to a time of competition. Races were run to show strength and endurance. Ceremonial races were run during the last phase of the moon to ensure its return. A game similar to soccer was played by kicking a stone for long distances. Sticks were thrown through hoops and targets. Rabbit stick throwing was for practice and sport. Catching acorn cap rings on a stick was a child's game. Games of chance were enjoyed by the Kumeyaay people. They played dice games. One was played by using sticks with decorations burnt, carved or drawn on them. One version of the game was to toss the sticks above a rock so the sticks bounced. Points were made by how many sticks landed with design side up. A similar game was played by teams wagering on flat side of sticks or rounded side. Peon was and still is a

game played by the Kumeyaay people. This was and still is a very

enjoyable time. It is played at night and can last for days until all

counter sticks are won. It is played by two teams. The object is to

hide the black and white bones or small sticks in each hand of one

team. They cross arms hiding the sticks from view. The other team

selects a killer who tries to guess where the white bones are by

motioning with his head. Counter sticks are used to keep score. The

game is played until one team has all counter sticks. Foreign Influences In 1769, the Spanish arrived and founded the Mission and Presidio of San Diego starting the destruction of the Kumeyaay way of life. In spite of several revolts, the Spanish guns and horses combined with introduced diseases to overcome the Kumeyaay. However, the mountain bands, under the national leader, the Kuchut Kwataay, kept lookouts on the mountain peaks and were generally able to flee their villages before the soldiers and padres arrived. The planting and use of wheat, new vegetable crops, fruit trees, and domestic animals spread beyond the area of Spanish control. Therefore, only those nearby, or in the large open valleys became subjects of the missions. By the time of mission secularization, the Kumeyaay population and dropped to about 3,000 persons. Under Mexican secularization, freed of mission control, most Kumeyaay fled to the mountains where they could not be forced to work for the Mexican settlers or army. Populations started to rebuild. Then the American army entered followed by settlers. Those bands along the emigrant trails and near San Diego were affected immediately. Some lost control of parts of their land; while others, for the first time, had a market for their crops and sold to emigrants and to San Diego settlers. Populations again dropped as resources were taken. Not until 1868, after the Civil War, were most of the Kumeyaay bands, especially the southern mountain bands, seriously affected by the entrance of settlers. Loss of Indian Land The year 1870 began a period of land expropriation from the Kumeyaay, especially their farm land and their water resource areas. While Capitan Grande, Sycuan and Inyaha were reserved for them by Executive Order in 1875, trespassers still tried to take the Indian's good watered farm lands. The plight of the inland bands was ignored until after the Indian Rights Association and the Sequoya League brought publicity to the situation forcing the Indian Agency to reserve and survey the lands of Cuyapipe, La Posta, Manzanita, and Laguna. The coastal Indian bands had no lands reserved but were told to go Capitan Grande. A few did. But most remained scattered working for non-Indians until Spreckels deeded the Jamul Indian Cemetery to the church and told the people living beside the cemetery that they could always remain there safely. This became a refuge for a number of coastal people. Jamul petitioned for federal recognition and eventually received it. The Kumeyaay population began to increase after 1910. |

|

San

Diego County & Baja California. Imagine San Diego with no buildings,

cars, or freeways. Just trees, plants, rivers, streams, mountains,

rolling hills, and abundant animal life that included deer, antelope,

and bear. A small picture of this can be gleaned if you hike along

trails and streams in the preserved mountains, canyons and parks in

the San Diego County area. Into this picture add 25,000 to 28,000

people, the Kumeyaay, living near the abundant streams and lakes.

Visualize many bare children picking berries and skirted woman picking

grasses along the stream. Men coming home with big horn sheep strapped

to their backs. These people lived in harmony with their environment

and the natural resources around them.

San

Diego County & Baja California. Imagine San Diego with no buildings,

cars, or freeways. Just trees, plants, rivers, streams, mountains,

rolling hills, and abundant animal life that included deer, antelope,

and bear. A small picture of this can be gleaned if you hike along

trails and streams in the preserved mountains, canyons and parks in

the San Diego County area. Into this picture add 25,000 to 28,000

people, the Kumeyaay, living near the abundant streams and lakes.

Visualize many bare children picking berries and skirted woman picking

grasses along the stream. Men coming home with big horn sheep strapped

to their backs. These people lived in harmony with their environment

and the natural resources around them. The

inhabitants going about their daily chores. Women with long black

hair, wearing bark skirts picking grasses along the stream. Babies in

cradleboards propped against a boulder or an oak tree. Children

picking elderberries while a group of older women sit near huts

weaving baskets.

The

inhabitants going about their daily chores. Women with long black

hair, wearing bark skirts picking grasses along the stream. Babies in

cradleboards propped against a boulder or an oak tree. Children

picking elderberries while a group of older women sit near huts

weaving baskets. were

used most for utilitarian jobs and many were plain. Others were

extremely beautiful and used for gifts and trade. The hat baskets were

used for head protection as well as adornment. The materials used to

make the baskets grew throughout the area. Bunch grass, deer grass,

juncus and three leaf sumac were used to construct baskets. Many

patterns were detailed and colored in shades from black to light

beige. Some of the must beautiful baskets were made with the beige and

black patterning. Often juncus was dyed black by burying or soaking

coiled juncus with crushed acorn caps. The tannin from the acorn

reacted with the iron in the water and would dye it black. Some of the

popular patterns were geometric designs and nature motifs as stars,

flowers, butterflies, deer and rattlesnake. Other Indian groups (ie.

Cahuilla of Palm Springs) that bordered the Kumeyaay area,north and

east, also had like basket designs and style. Indian of the Oaks makes

excellent references as to how to make baskets.

were

used most for utilitarian jobs and many were plain. Others were

extremely beautiful and used for gifts and trade. The hat baskets were

used for head protection as well as adornment. The materials used to

make the baskets grew throughout the area. Bunch grass, deer grass,

juncus and three leaf sumac were used to construct baskets. Many

patterns were detailed and colored in shades from black to light

beige. Some of the must beautiful baskets were made with the beige and

black patterning. Often juncus was dyed black by burying or soaking

coiled juncus with crushed acorn caps. The tannin from the acorn

reacted with the iron in the water and would dye it black. Some of the

popular patterns were geometric designs and nature motifs as stars,

flowers, butterflies, deer and rattlesnake. Other Indian groups (ie.

Cahuilla of Palm Springs) that bordered the Kumeyaay area,north and

east, also had like basket designs and style. Indian of the Oaks makes

excellent references as to how to make baskets.