| |

|

Woodland and Mississippian TRADITION

(see Woodland and Mississippian

VESSEL FORMS & TECHNIQUES

below)

|

| |

|

|

|

|

THE WOODLAND

TRADITION

The Woodland Tradition is

generally distinguished from the earlier Archaic Tradition by the

construction of burial mounds, the advent of rudimentary cultivation,

and by the presence of cord and fabric marked pottery types. This

began around 700 BCE and reached its climax about 100 BCE. Remnants of

the Woodland tradition lasted into the modern era.

The Woodland Tradition is

divided into two periods. The first, Burial Mound I, dates from

700-300 BCE, and is best represented by the Adena culture of the Ohio

Valley. Sites are marked by burial mounds and/or earthworks. A cult of

the dead seems to have been a major part of Adena life. Away from the

burial centers, small villages of three to five houses prevailed.

Ceramics were simple in form, with cord or fabric marking and

occasionally incised decoration.

The second period, Burial

Mound II, spanned from around 300 BCE to 700 CE. This period saw the

rise of the Hopewell culture, which was little more than an

elaboration of the earlier Adena culture, and the dividing line

between them is not very clear. Earthworks were larger and more

complex, burial mounds were larger, and ceramics forms more

sophisticated and varied. Specialty vessels were developed

specifically for ceremonial use. Hopewell culture was carried

throughout the Upper Mississippi and Missouri valleys. |

|

http://www.beloit.edu/~museum/logan/mississippian/introduction/woodland.htm |

|

|

|

|

|

Mississippian Cultures |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

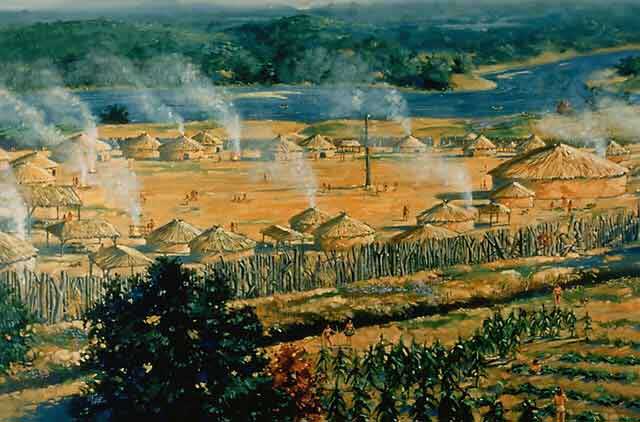

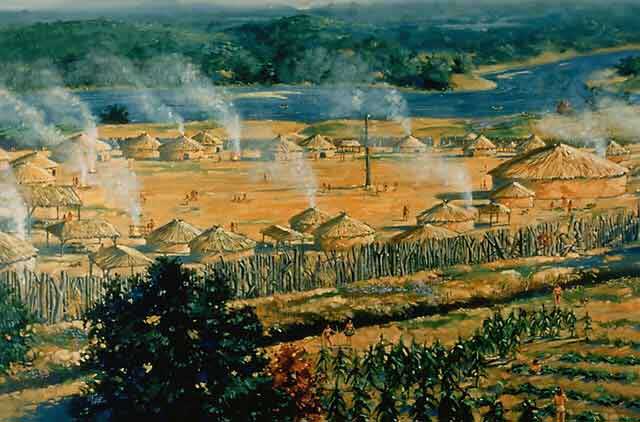

THE MISSISSIPPIAN

TRADITION

The

Hopewell culture began to fade near the end of the Burial Mound II

period. Around 700 CE a new tradition known as the Mississippian was

forming in the area of northeastern Arkansas and southeastern

Missouri. For the purposes of this exhibition, this region will be

referred to as the "core area". There were substantial differences

between Mississippian sites and their Woodland predecessors. Sites

were marked by flat-topped mounds upon which temples and important

buildings were constructed. As such, the Mississippian Tradition is

divided into Temple Mound I and Temple Mound II periods. In contrast

to the Hopewell sites, burial mounds became far less significant.

Agriculture intensified considerably with the introduction of better

strains of maize, which resulted in a far more sedentary lifestyle.

New vessel forms arose along with new types of decoration. Shell

tempering became the norm. Many of these characteristic features

clearly indicate Mesoamerican influence. The relatively smooth and

slow transition from Woodland to Mississippian traditions indicates

that this influence was not direct, but absorbed gradually over time.

The Mississippian tradition is best represented by the site at

Cahokia, in southern Illinois. The Temple Mound I phase is not well

understood, but it appears to have been the continuation of a trend

towards nucleation into large centers, but now these centers took on

a form more like their Mesoamerican counterparts. From Cahokia other

sites were "colonized" in outlying areas, such as Aztalan in

Wisconsin, Obion in western Tennessee and Hiwassee Island in eastern

Tennessee, and Macon, Georgia. Contemporary developments were

occurring

in the Lower Mississippi Valley, with the Coles Creek cultures of

Louisiana and Mississippi. These were similar to the Cahokia types,

and exerted influences eastward into Florida and Georgia and westward

up into the Caddoan regions along the Red River.

The Mississippian Tradition reached its zenith between 1200 and

1500 CE. Areas which had at one time been a mix of Mississippian and

Woodland traditions now became predominantly Mississippian, yet they

retained the differentiation created by their varying Woodland

heritages. Cahokia continued to expand, and larger sites proliferated

in the core area of southeastern Missouri and north- eastern Arkansas.

In the Ohio Valley, Hopewell lifestyles gave way to a more sedentary,

Fort Ancient variant of the Mississippian. The influence of

Mississippian culture can also be found to the northwest, in the

Oneota culture which fused earlier Woodland traditions with the new

imports. Ceramics forms continued to expand and now included far more

sophisticated forms, such as effigy vessels, and various types of

painted decoration.

The development of the Woodland and Mississippian Traditions can

best be traced in the evolution of pottery forms through time. By

measuring changes in vessel forms and decorative techniques, it is

possible to understand just how the peoples of each region combined

the elements of these two traditions into their own local variants. |

|

http://www.beloit.edu/~museum/logan/mississippian/introduction/mississippian.htm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Excellent information

from the Logan Museum

of Anthropology on line from

Beloit, Wisconsin |

|

All text and images are used courtesy

of the Logan Museum of Anthropology, Beloit College

(

http://www.beloit.edu/~museum//logan/index.html).

All objects illustrated are in the permanent collection of the Logan

Museum. |

|

|

|

Woodland and Mississippian VESSEL

FORMS

|

|

Ceramic production was a

relatively new concept during the Woodland Period, and there was

not a tremendous variety of vessel forms. In fact, bowls were

often carved from soapstone rather than being ceramic, and those

which were ceramic were of the simplest types.

|

|

Jars were by far the

most common vessel form during the early period. Some had flat

bottoms or were provided with four short legs. The most common

type, however, was the "conoidal-based" pot, seen at left. This

form is an indicator of the Woodland Period, as later it was

rather uncommon. |

|

A far greater variety of vessel forms existed during the

Mississippian Period. Bowls were made from clay rather than stone.

Forms ranged from wide, shallow types to globular bowls with

slightly incurving rims. The rims of most bowls were either

beveled or provided with simple filleted decoration. Some bowls

also had flared rims which were decorated in some manner along the

exterior of the rim.

|

|

A jar is distinguished

from a globular bowl in that its opening is more constricted, and

may also have a short neck. The globular jar seems to have been

the most prevalent type, generally provided with a short rim or

neck. Lugs, which are loops added to the rim through which a cord

might be run to suspend the pot, were common features. Jars with

necks tend not to have lugs, as they could usually be grasped by

the neck. The deep jar, similar to the conoidal-based jars of the

Woodland Period, remained, but now usually had the characteristic

rim and slightly flattened bottom.

|

|

Bottles differ from jars

in that they have much longer and narrower necks. They were used

to store water, and were most often utilitarian and undecorated.

Those which were used for ceremonial purposes, however, were

provided with painted or incised decoration.

|

|

The hooded "bottle" is

really more like a globular jar, but the very constricted opening,

provided in the back of the "head" of the vessel, places it in the

bottle category. Hooded bottles are invariably small - about 4" to

7" tall - and are nearly always in the form of some animal or

human.

|

|

One of the unique

features of Mississippian pottery, as compared with earlier

Woodland types, is the prevalence of effigy vessels, that is,

pottery which is made in the form of an animal or human. Common

subjects are those found in the everyday life of river peoples -

fish, beaver, opossum, shells and wildcats.

Humans effigies were also very popular, often only distinguishable

by a face. The most peculiar effigy type is the hunchback. This

deformity must have been fairly common, and those afflicted were

often revered as shamans. |

| |

The tremendous variety of vessel forms was matched by an equal

variety of techniques employed in their decoration...

|

|

|

http://www.beloit.edu/~museum/logan/mississippian/introduction/vesseltypes.htm |

|

|

|

|

DECORATIVE

TECHNIQUES

|

|

Mississippian vessels

were generally constructed using the coiling method. Hand-rolled

coils of clay were built up from the base to create the general

form of the vessel. The vessel was then smoothed on both the

interior and exterior. Often additional texture or decoration were

added to the exterior before firing. Once fired, the pot might be

further polished using a clay polisher like those depicted at

left. I have seen them referred to as "trowels" and "polishers",

indicating that scholars are unclear as to whether they were used

to help fuse together the coils during construction, to brighten

up the finish of a fired pot, or perhaps both.

|

|

All ceramic vessels are

created with clay to which some binding agent, called temper, has

been added. This gives the vessel far greater strength. The

earliest vessels in the Southeast were tempered with fibers of

grass or roots. By the Woodland Period, mineral tempers became the

norm. Grit, crushed rock, sand or ground ceramic sherds were the

most common types.

|

|

Fabric Marked vessels

have a rough surface whose texture resembles that of a textile.

This is because the vessels were smoothed before firing with a

wooden paddle wrapped in fabric. Once smoothed, the paddle was

pressed against the vessel to provide the characteristic texture.

|

|

Cord Marked vessels were

prepared in the same manner as Fabric Marked pottery, except that

the wooden paddle was wrapped with cord rather than fabric. This

resulted in a finish which resembled incising, except that the

lines are usually curved and very closely spaced, and their ends

nearly always overlap.

|

|

Sometimes paddles were

carved with some sort of curvilinear pattern, which created a

surface which was far more decorative. This decorative technique

was particularly popular in the Swift Creek area of central

Georgia. I suspect these textured types of "decoration" were in

fact an effort to increase the handleability of the vessel, as

they usually occur on pots without handles.

|

|

Rocker Stamped vessels

have patterns created by rolling curved "rocker stamps" over the

surface of the vessel. Rocker Stamps usually create the appearance

of regularized pinpricked decoration, and are often applied in

linear or curvilinear patterns.

|

|

One of the major

distinguishing features of the ceramics of most Mississippian

cultures was the wholesale adoption of shell tempering. The use of

crushed shells apparently had a number of advantages over mineral

tempers. Chemical reactions created during the firing process made

the vessels even stronger than before. The shell also aided in

heat transfer, making cooking vessels far more functional. Shell

temper is often visible on the exterior, making it an easy

indicator.

|

|

Punctated designs are

those which were punched into the surface using some sort of sharp

tool or even the fingernail. Usually the indentations are not very

deep and are either conical indicating an awl-like tool, or

elongated and rectangular indicating a narrow flat tool. The

example at left is somewhat unusual in this regard.

|

|

Incised decoration was

created by drawing linear or curvilinear patterns on the unfired

clay. Incised decoration is distinguishable from engraved

decoration by the buildup of excess material along the edges of

the incised lines. This is visible in the example at left.

|

|

The use of noding was

limited to a fairly small area in the core region of Mississippian

culture. Nodes are small balls of clay which have been added to

the surface of the smoothed pot. Two varieties are found, the

first having nodes situated in an allover pattern, the second

having one or two distinct rows of nodes placed near the rim.

|

|

When patterns were

created by adding raised designs in clay to the surface of a

smoothed vessel, it is termed "appliqué". Noding might be thought

of as a form of appliqué, but the typical form creates some

variety of linear patterning. Zigzag is common, especially along

rims, and beaded rims are also considered to be of this type.

|

|

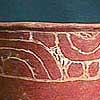

Engraved decoration was

created by scratching away at the surface of a vessel which had

already been fired, revealing the natural color of the clay below.

This must be done with a very sharp tool, and as such, solid areas

of engraved design always show telltale scratch marks created by

the tool, and are often not even completely cleared of the surface

color, as seen at left.

|

|

All of the previously

mentioned decorative techniques have been "plastic", meaning that

they were modifications to the actual clay of the vessel. Painting

is a surface decoration, and was usually added to the vessel after

it had dried, but before it was fired. Red and white were the most

popular colors, black being a late addition.

|

|

Negative painting

involved painting the majority of the vessel some background

color, usually black, but leaving the linear design unpainted.

After the vessel was fired, the natural clay color remained light,

showing through as the pattern color. This was often enhanced with

the addition of a third color, usually red, to complete the

design.

|

| |

With this background in

the traditions of the early peoples of eastern North America and

their techniques ceramic production behind us, we can now better

appreciate the artifacts themselves... |

http://www.beloit.edu/~museum/logan/mississippian/introduction/techniques.htm |

|

|

|

| |

|

ClayHound Web

- Woodland - Mississippian

Pottery

ClayHound Web

- Woodland - Mississippian

Pottery